by Meryl Marshall (NOSAS)

Over the years tradition has had it that there are the remains of a distillery dating back to the 18th Century at Mulchaich Farm, located in the district of Ferintosh on the Black Isle. The distillery site is about 200m NW of the farm and was previously unrecorded; it was in a sorry state being quite overgrown with whins and with the few open areas grossly trampled by cattle. In 2009 members of the North of Scotland Archaeological Society began a project which had as one of its aims the surveying and recording of the distillery site and that of the neighbouring chambered cairn (HER MHG 9083). The project also included a limited amount of historical documentary research following which a report was produced – see also Appendix II below for further details.

It was felt that together with the chambered cairn the distillery site would make an interesting and attractive place for people to visit. The landowners, the Dalgetty family, were happy to oblige with permission and for this we are very grateful. In addition the Adopt-a-Monument Scheme hosted by Archaeology Scotland were keen to help us with advice and limited funding, so in October 2012 NOSAS began a second phase of work at Mulchiach, preparing the site for public presentation. It is this later project that forms the chief focus of the following article.

Mulchaich Farm, distillery site (west settlement) and chambered cairn – Aerial photo taken from the north

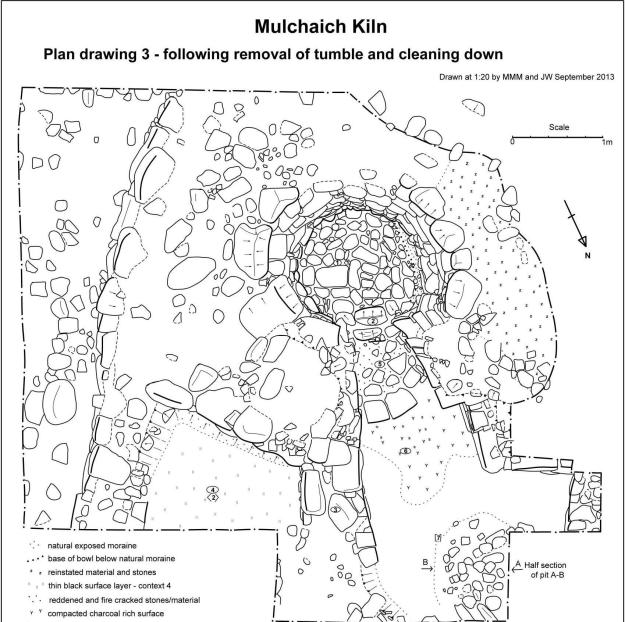

The Mulchaich Kiln

The main thrust of the work during the summer of 2013 was targeted at the kiln where the barley or bere, which had been allowed to germinate, would have been made into malt by gently heating it until it was dry . The kiln had all the characteristics of a corn drying kiln and the purpose of our exercise was to clear the rubbish that was inside it so that its features could be displayed and we could interpret them for visitors. The work was carried out as if it was an excavation; nothing structural was removed, everything was recorded as we went along, photographs were taken at all stages and a report was subsequently published.

The kiln bowl had been constructed on a small mound of glacial till which had been levelled off to form a platform. The platform was built up on the east side and reinforced with boulders and the kiln bowl itself was sunk into the natural morainic till by 200mm; likewise the flue and the area in front of the entrance which was sunk by 500mm.

The kiln bowl was just like any other at the many corn drying kilns seen at Highland townships, however the flue was quite different to the usual type of small to moderate sized bore vent seen in corn drying kilns. It was large by comparison and had walls that were substantially built. An unusual feature was a sloping setting of three stones with distinct edges at the exit of the flue; it “tipped” away from the bowl so that it would have directed the warm air coming from the flue upwards through the kiln.

At the south end of the flue – there was substantial evidence of a hearth within the flue. A paved area of degraded, reddened and fire-cracked stones extended for 1m to the level of the rebate in the west wall. The walls too at this point were grossly affected by heat with substantial reddening and with the wall cheeks hollowed out by some 75mm to 100mm due to fire cracking and crumbling of the stone work. work both on the paving and on the walls. In front of the hearth there was clear evidence of rake out material from the hearth with a compacted charcoal rich ash surface.

The flue, post excavation, from the east with the reddened and fire cracked paved hearth and walls – note also the “tipping” stone feature to the left

The pit in front of the flue entrance had been dug a further 600mm into the natural glacial till. Resting at the bottom, under a dark brown organic rich soil, was an iron object, buckled and corroded it was apparently a suspension device of some kind, 500mm long with 3 links, the middle one of which is a swivel. No evidence of burning was found in the pit.

Discussion

Many ideas and theories have been put forward as to the position of the heat source and the nature of the drying process. Two are outlined here and both have drawbacks.

One theory is that the site of the fire, called a furnace in this case, was originally intended to be in the flue as this would give the greatest heat to dry what must have been a significant amount of grain/malt but it is difficult to imagine that this would be done in the knowledge that the walls of the flue/furnace would succumb to the heat, also that there was a danger that of the whole thing to go up in flames because it was so close to the kiln.

Another theory is that the fire within the flue was part of the final phase of the kiln; it had not been the original intention for the fire to be in the flue. When the kiln was constructed originally the firepit had been positioned further back outside the entrance to the flue, where the pit 60cms deep had been dug into the natural. But this position had proved to produce an ineffective heat source for drying the required amount of malt/grain and the fire had been moved closer to the kiln bowl. The problem with this theory is that apart from a few pieces of charcoal no substantial evidence of burning was found in the pit.

It is well documented that corn drying kilns were used for malting when distilling was a cottage industry and before the development of the malt kilns that we know today (as at Dallas Dhu distillery). “Our” kiln seems to be somewhere in between – a transitionary stage of malt kiln? a fore-runner of the malt kilns? See Appendix II below for further discussion of the kiln with diagrams.

The excavation and consolidation of the kiln was completed in early October 2013 and the Mulchaich site was informally opened for visitors at the Highland Archaeology Festival Conference with the production and distribution of the Mulchaich distillery leaflet. The leaflet has a brief description of the site and invites people to find out more by visiting it and scanning a QR code which is linked to our website page. The full report can be found here.

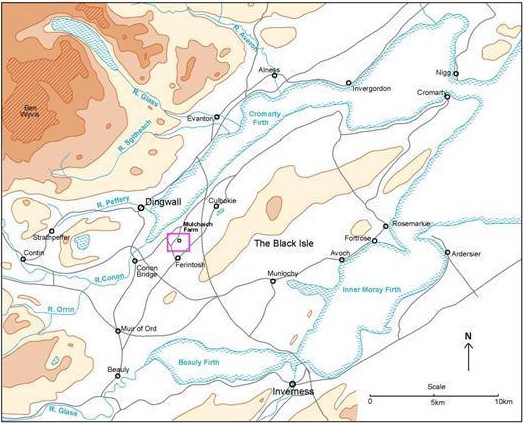

Location and Directions

Mulchaich is situated on a NW facing slope of extensively farmed agricultural land above the Cromarty Firth in the western part of the Black Isle. It has panoramic views towards Dingwall and Ben Wyvis. The site is just 2 miles NE of Conon Bridge and approached by minor roads between Easter Kinkell and Alcaig, east of Conon Bridge. It is close to the Ferintosh Free Church at grid reference, NH 576 568. Parking is in the Ferintosh Free Church car park, however we request that you avoid Sunday mornings and evenings when the car park gets very busy. From the car park there is a 300m walk – go north and take a right turn, signposted “Mulchaich”. Walk up to the farm. Access can be made from the first gate on the left from the farmyard.

Please keep dogs on leads on the site as the enclosure is used for grazing sheep.

And beware of the various trip hazards – the ground is rough, steep and uneven in most places

Above: Drone images processed with photogrammetry by Andy Hickie, following site clearance by NOSAS in November 2022.

Appendix I: A brief description of the processes involved in distilling whisky

The ingredients required for making whisky are grain, usually barley (or in earlier days bere, an ancient form of barley), a constant supply of running water and a plentiful supply of peat. The barley is allowed to germinate into malt which is then dried by gently heating it. The dried malt is milled to make “grist”, and this is then mixed with hot water to make “wort”. The “wort” is fermented and the resulting “wash” is heated up in a still, preferably made of copper. The alcohol vapours given off are cooled by passing them through a “worm” which has cold water running over it and the spirit is collected from a spout at the bottom of the “worm”. For more information on production of modern whisky click here or visit Dallas Dhu distillery which is in the care of Historic Scotland,

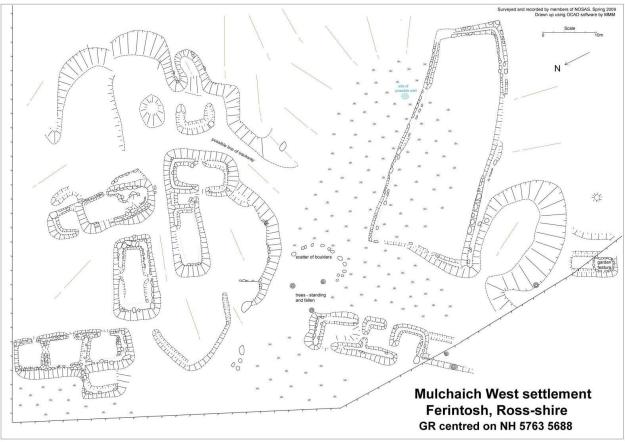

Appendix II: The site of the Distillery at Mulchaich Farm – NOSAS Project 2009/10

Initially the site was quite overgrown and the first task of NOSAS members was to clear the whins and vegetation so that a better look at the features could be achieved. We were then able to survey the site using a combination of plane table and taped offset methods. This plan was the result of our survey:

The marshy area at the centre of the site and its spring fed well would have been a pond which provided the water essential to the distilling process; the drainage of the area has been significantly altered by more recent field drains, the pond is now silted up and appears as a bog. The central part of the bog has a firm base and systematic probing of it indicates that there are the remains of an embankment in its lower part.

The remains of seven buildings were revealed; all had substantial dressed stone foundations and it would appear that the majority had been constructed to a plan. From the solid nature of the buildings and their uniformity it is quite possible that this was one of the distilleries that John Forbes built in the 1760s or perhaps in 1782. We can only speculate as to the purpose of the seven buildings but it is possible to determine the function of some of them. The still-house was probably the building with several compartments below the pond; it is possible that a wooden lade ducted the water from the pond into this building. Almost certainly some of the other buildings would have been for storing the grain.

A kiln with a barn of two compartments is located in the north part of the site. Outwardly the building has the charecteristics of a corn-drying kiln and it is well documented that corn drying kilns were used for malting in the early days. Corn drying kilns, as is evident from the name, were normally used for drying corn and were an essential part of all Highland townships where the climate could not be relied upon to dry the corn sufficiently for it to be ground into flour or meal. The grain would have been laid out on a grid or perforated floor on top of the kiln bowl, warm air provided by a fire on the outside (but inside the kiln barn) and ducted by a small flue into the bowl, was drawn up through the grain thus drying it. The sketches are of a corn drying kiln in Glen Banchor, near Newtonmore, which was excavated and reconstructed at the Highland Folk Museum, Newtonmore.

In the 18th century malt kilns as we know them in modern distilleries had not been developed. When we excavated the kiln bowl at Mulchaich it proved to have an unusual flue. The flue was substantially constructed and was much wider and bigger than was normal for a corn drying kiln; in addition the fire platform was inside the flue and much nearer to the kiln bowl itself; there was an interesting stone arrangement which would have directed the warm air up through the kiln. Was this a transitional form of malt kiln? Later malt kilns had the fire, with a heat deflector above, directly under the malting floor and the floor was much higher, presumably to reduce the risk of the whole lot catching fire – see sketch. Together with the oral tradition of this site being used to distil whisky the archaeological features are pretty convincing.

Appendix III: Ferintosh Whisky and the history of Mulchaich

It is a well-known fact that Ferintosh had a thriving whisky industry 300 years ago. It was to continue for nearly 100 years and when the duty exemption privilege was withdrawn in 1786, such was the fame that Robert Burns was moved to lament in his poem “Scotch Drink”:

Thee Ferintosh! O sadly lost! Scotland lament frae coast to coast! Now colic grips, an’ barkin’ hoast May kill us a’; For loyal Forbes’ charter’d boast Is taen awa’!

The oral tradition of Mulchaich having a distillery is widely held both by local people and by the former landowner who himself is a direct descendent of Forbes of Culloden. We have found no firm evidence of the site being used to produce whisky however and there is no firm documentary evidence linking Mulchaich with the production of Ferintosh whisky. But there are lots of tantalising features about the site which lead us to believe that distilling was carried out on an industrial scale and there are vague references in documents to barley being imported to Mulchaich.

An ongoing blind search of the warrants of registered deeds threw up the following bill (with thanks to Malcolm Bangor-Jones):

“At Cromarty 28 March 1733 Alexander Mackenzie in Mulchaich in Ferrintosh, Robert Mackenzie there, Donald Fowler there, and Colin Simson in Cromarty (of whom only Robert could sign) ‘signed’ a bill that they would on 15 May pay Mrs Margaret Mackenzie £128 Scots for “value received in sufficient bear (bere)”. The bill was protested for partial non payment on 8 November”.

And another by the same parties “Cromarty 28 March 1733″ to pay £170 Scots “value received by you in sufficient bear”

Almost certainly the bere was being imported to Mulchaich to make whisky.

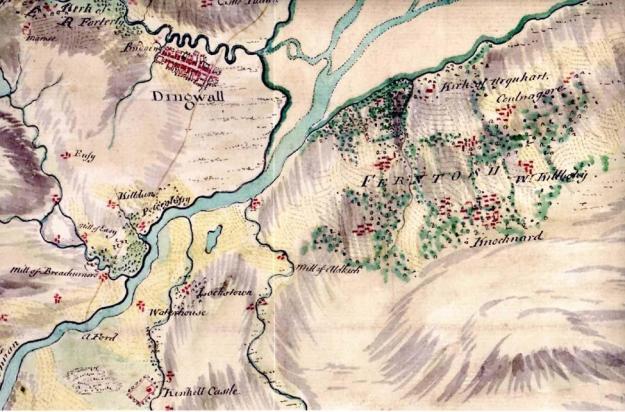

The Roy military map of c1750 has a densely populated area at Ferintosh, with at least 7 large townships. A township at Mulchaich is not mentioned by name but almost certainly the township in the southwest of the group is in the position of Mulchaich.

About 400m to the NE of the farm there is another settlement site, which would have been in existence at the time. Scheduled by Historic Scotland and very different to the distillery site it comprises the turf footings of 9 or 10 buildings arranged in two parallel rows – this was an earlier township where a distilling would have been done as a cottage industry in 1750. This township probably continued to provide accommodation for the workers at the distillery site when it was built in the 1760s or in 1782. Interestingly a George III (1813-1819) penny was found between this township and the distillery site during a fieldwalking exercise.

Further information on Mulchaich can be found with the following references:

A Project to Identify, Survey and Record Archaeological Remains at Mulchaich Farm, Ferintosh, Ross-shire February 2009 – May 2010 (NOSAS Report)

Visit Mulchaich Distillery, (NOSAS website page)

Mulchaich Ferintosh Project 2012 (NOSAS Website page)

Case Study: A possible 18th century distillery site at Mulchaich Farm, Ferintosh (SCARF)

In the 17th century there was a shift from using peat or straw to drying grain/ malt to using coke or coal which produced less smoke. A straw or peat fire was usually set on a long flue due to the risk of sparks igniting the drying floor. Coke/coal fires could be set directly under a higher floor. This kiln might be a transitional type between the peat and coke kilns.

The first step in malting is soaking the grain for up to 48 hours in water. Is it possible your mystery pit was used to soak grain, and the metal object used to move heavy water ladened grain sacks about? The pit need not be water tight as they’d have wanted it to drain after the soaking was done. How would worms feel about grain infused water?

The next step is to spread the wet grain in a cool dark place to germinate, usually on a hard packed earthen floor. Isn’t that what you have with your thin black surface at context 4?

Looks like a malt works to me.

LikeLike

Very cool. One day, I will have to go there. I am actually descended from Colin Simson, as I just found out. 🙂

LikeLike