by Duncan Kennedy (NOSAS)

Dun Deardail (Canmore ID: 23727, HER: MHG4348) is a hillfort located at a height of 1,127 ft (347m) on a prominent knoll on the western flank of Glen Nevis (Figure 1). It is thought that it was originally occupied in the Iron Age, and saw later periods of reuse by the Picts. August 2015 saw the first ever archaeological excavation of the site, as the first of three seasons of the Dun Deardail Archaeological Project, which forms part of the ambitious Nevis Landscape Partnership.

Figure 1: Dun Deardail, centre, sits in a commanding location above Glen Nevis (©2011 FCS by Caledonian Air Surveys)

Although currently known as Dun Deardail, the site has in the past been known by a variety of names – it’s Dundbhairdghall on the 1873 OS map for example, and has also been noted as Deardinl, Dun Dear Duil and Dun Dearg Suil. The meaning of the name is uncertain, and the site has been tenuously linked with Deirdre, a tragic heroine of Irish legend who fled to Scotland.

Dun Deardail is one of Scotland’s many vitrified forts (see also our blog post on Craig Phadrig), where the walls have been subjected to burning so intense that some of the stones have fused together. Vitrification has been the subject of much debate, with proferred theories including it being either accidental or the result of attack. However, it requires that very high temperatures are sustained for long periods, so the fires would need to have been carefully managed and maintained – possibly for several days. This suggests that the process must have been intentional, but questions still remain. Were these fires built by an enemy after capturing the fort, for example, or was this a ritual act of closure of the site marking the end of its use? One thing for sure is that the fires would have been spectacular, particularly at night, and would probably have been visible for miles. Part of the project involves the University of Stirling, in partnership with Forestry Commission Scotland, investigating the process, purpose and significance of vitrification in the Scottish Iron Age and Early Historical period.

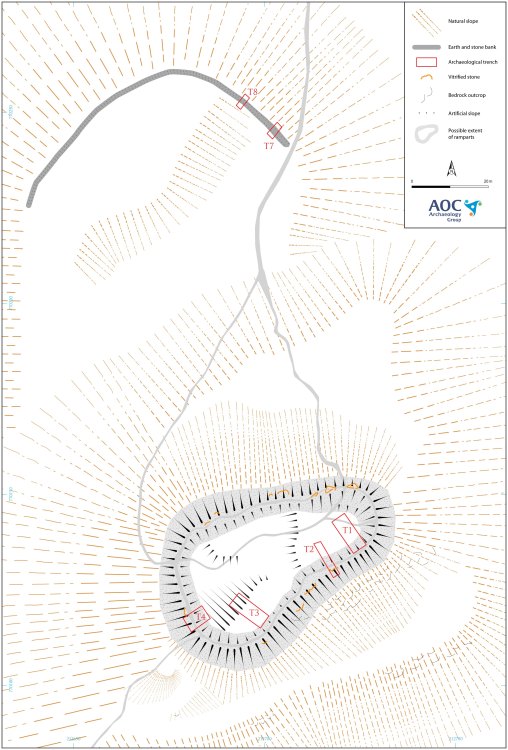

The first season of excavation saw the opening of six trenches (Figure 2). Four of these were located inside the fort, of which two were in the inner “citadel”, and the other two were opened across an earth and stone bank on the terraces below the fort.

Trench 1 extended from the wall into the upper citadel area of the fort. It contained a hearth, and some hammerscale – which may indicate that metal working was undertaken in the upper part of the fort. Further evidence for metal working activity in the vicinity of the fort was found in the form of a crucible. Beautifully glazed from use in the working of non-ferrous metals, it was discovered before the excavation even got under way, during construction of the new path to the site (which can be seen in Figure 5).

Trench 2 was opened across the wall and into the citadel area, and was found to contain burnt cereal grain underneath a layer of charcoal. The grain was partially processed, and may indicate the storage of surplus produce within the citadel. If so, could this be the first evidence for such storage in a Scottish hillfort?

Trench 3, inside the lower part of the fort, contained post holes and stone built post pads for a rectilinear building. Although no direct dating evidence has yet been obtained for this structure, the form of the building would tend to suggest that it dates from the Early Historic period.

Trench 4 was opened across the wall in the south western part of the fort. Both this trench and trench 2 revealed important details about the construction of the wall and its collapse. Vitrification seems to have been largely limited to the upper portions of the wall core in both trenches, and in trench 2 there were very clear voids left from the timbers that had featured in the construction (Figure 3).

Figure 4 uses both the archaeological section drawing to illustrate the spread of collapsed rubble and a reconstruction drawing to illustrate the possible timber and thatch superstructure in both section and in 3D. The destruction process is indicated by the arrows: [1] the timber superstructure collapses and heats the upper part of the wall (creating the molten vitrified core); and [2] the rampart walls then collapse outwards (creating the rubble deposits). The outer rampart wall has not yet been recorded and the rampart may have been wider.

The 2015 excavation has already revealed Dun Deardail to have been a high status site, with evidence suggestive of metal working and the storage of agricultural surplus. This season, trenches 2 and 3 will be reopened and will be the focus of research into the earlier history of the fort. Research into vitrification will continue, and other areas of investigation will be the terraces, and an examination of the differences between the upper citadel and the lower part of the fort.

The Dun Deardail Archaeological Project is funded by Forestry Commission Scotland and the Heritage Lottery Fund, in partnership with AOC Archaeology and the University of Stirling. Following a comprehensive Project Design, the professional archaeological excavation includes volunteer training opportunities, public outreach and associated educational provision for local schools and will culminate in both popular and academic dissemination of the results.

The project is proud to promote the aims and objectives of Scotland’s Archaeology Strategy and is designed to contribute to the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework. This season, excavations start on Monday the 15th of August and continue until Friday the 26th.

There will be an open day as part of the Dun Deardail Archaeology Festival on Saturday 20th August, in the Braveheart Car Park in Glen Nevis. This will offer a chance to see the excavations, as well as take part in a variety of fun, free archaeological activities and demonstrations with the team from The Crannog Centre, including woodworking with replica ancient tools, basketry and ancient cooking. It should be a great day!

With thanks to Matt Ritchie (FCS) and Martin Cook (AOC).

Fascinating! There is a vitrified fort near where I live in Co Cavan, Ireland, but I understand there are not many of them over here.

LikeLike

Yep, I still think that the Deirdre connection is the strongest for the placename, as it also takes into account local consonant shifts ‘r’ > ‘l’. Are there plans for FCS interpretation panels at the sight at the end of the excavation?

LikeLike

I see Archeology still does not entertain meteor/asteroid pass as a possibility for vitrification in high places. Yet there is lots of evidence to show an asteroid in 562AD in Scotland. Beaumont, Velikovsky, Wilson, Blackett all show this possibility. Anyone would think there was a papal bull declaring the theory anathema, it is so well ignored….

LikeLike

the vitrificatian could be part of an old heliolatry, similiar to the direction of the walls. The south wall was orientatet to the summersolstice and the north wall to a date, comparable to the roman ceres celebration.

LikeLike

I visited the fort last March and had an overwhelming sense that it was positioned to catch the wind. It’s not that good a defensive position and I wonder if it was used for cooking metal ores prior to smelting the metals.

The sloped track would allow large quantities of ore and timber to be dragged up there and the long term burns would explain vitrification.

The walls also looked wrong for a defensive fort and your finds of crucibles would be consistent with this use of the location.

Fires would be force fed by the wind blowing up the valley to cook down the raw ores mined from the surrounding mountains. Plenty of wood available in the adjacent lower lying areas too.

Something to think about in your next digs. I will see what else I can find.

LikeLike

The vitrification bit and wall fire doesn’t sit that well with me…..Be interesting to see it reproduced to back up the theory…….

LikeLike