The following is based on a transcript of notes by Mary Peteranna (AOC) for her presentation at the Highland Archaeology Festival Conference 2015. It describes fieldwork at Craig Phadrig hillfort carried out by AOC Archaeology in early 2015 on behalf of Forestry Commission Scotland, see Data Structure Report.

Craig Phadrig (Canmore ID 13486, HER MHG 3809) is located on the west side of lnverness, a prominent position overlooking River Ness and entrance to the Beauly/Moray Firth. The Beauly Firth marked a southern boundary of an area defined in the north by the Dornoch Firth landscape, supposedly held by the Decantae tribe in the lron Age as shown in Ptolemy’s map. Knock Farrell and Ord Hill hillforts are in line of sight, and a third possible fort is at Torvean In Inverness (Canmore ID 13549, HER MHG 3749).

Aerial view of Craig Phadrig, Inverness, the Kessock Bridge and Ord Hill (Forestry Commission Scotland).

A visualisation of the same scene as it might have appeared in prehistory (Forestry Commission Scotland).

Craig Phadrig is a prominent landscape feature, referred to at the time of James Vl in 1592. It is an oblong fort, a type which clusters around the Moray Firth region. Similar forts in East Scotland such as Finavon, Dunnideer and Tap o’ Noth also feature lack of entrance and massive walls suggesting an exclusive use. Many show evidence for lron Age construction, abandonment and secondary re-use.

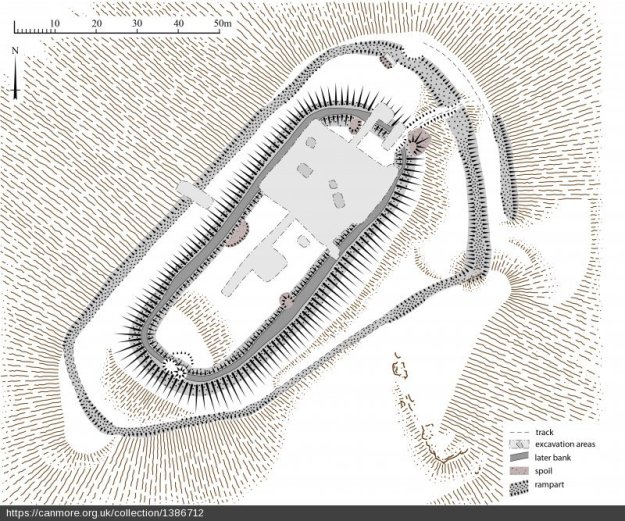

Previous survey and excavation. Numerous previous surveys have been conducted on Craig Phadrig, probably sparked by Penant’s 1769 Tour of Scotland where he mentions vitrified stone. Plan shows the 2013 RCAHMS survey with the estimated area of these excavations.

Craig Phadrig. Plan of fort incorporating results of RCAHMS survey (Sept 2013) and earlier surveys (Canmore).

Finally, in 1971/72 Alan Small and Barry Cottam dug for two seasons, from which only an interim report after the first season was produced. lmage of the inner rampart from 1971; Small found that the inner rampart had been built sometime in the 4th Century BC and that the wall core was significantly vitrified. He also noted significant disturbance by other earlier excavations.

In the interior North East he found a structure overlying an earlier one c. 3rd-2nd C. BC; an upper layer containing animal bone, peat ash and charcoal and from it came the late Pictish finds of the escutcheon mould for a hanging bowl, and distinctive E ware pot from that period. The Lower occupation layer contained a bronze pin.

Small then stopped and concentrated on the exterior. He suggests that the outer rampart was unfinished and the technique abandoned; but RCAHMS later suggested the outer rampart was earlier and perhaps robbed partly for inner rampart. The South West outer end was vitrified; Small believed there was no outer rampart in the North West, just a revetment at the NE end and that the third bank was created out of upcast from the outer wall. – At a later date, Seven radiocarbon measurements were taken; date ranges were 800 BC – AD 100, 550 BC – AD 350 and AD 200-800.

Clay mould for the escutcheon of a hanging bowl from Craig Phadrig 1971 excavation. Plan view, scale in cms (Canmore).

The 2015 Excavation. Mary Peteranna and Steve Birch were asked to excavate erosions caused by fallen tree in the northern corner of the inner rampart. A trench was placed to expose the extent of the damage to the rampart and to assess the nature of surviving archaeological deposits. The exposures had removed a lot of stone, but it wasn’t evident exactly what damage had been done until the exposures and the trench had been excavated.

The North East exposure revealed slight darker discolouration, mostly reddened wall core and a line of boulders in front forming a structural kerb, part of which had been pulled away by the disturbance. The South West exposure had been more destructive revealing a reddened wall core with a real mix of fragmentary loose material, cobbles and sand core. It did not look vitrified but appeared to have been intensely heated from the reddened, heat-cracked nature of the stones.

In addition an evaluation trench was excavated perpendicular to the tree exposures over the rampart bank. The rampart profile showed a distinctive upper bank with a ditch and a lower bank. The pre-excavation image below shows the separation between two banks on top of the rampart, divided by a central slot.

The upper banks comprised a mixture of heat-affected and unburnt stone overlying compact areas of vitrified stone. These were divided by a ditch containing virtually no vitrified stone, suggesting that this was a later insertion.

The ditch had a lower fill of compact stones, possible post-settings at either end suggesting a post arrangement supported by perpendicular planks. The V-shaped profile of the ditch, packed with stone, combined with two opposing stone settings suggesting this was a palisade ditch – a ditch inserted into the rubble of the vitrified fort, built later than the destruction of the hillfort.

Post excavation image showing the upper rampart banks and ditch in section; posthole (to far left); facing WNW (AOC).

The primary wall core was represented by heat-affected and vitrified stone and loose core; linear banks of larger stones appeared to form structural supports for the wall construction. These represented the building technique involved in construction of the rampart; a solid base for packing smaller looser core in and possible smaller stones for bedding in the timber supports. Much of this was clearly heat-affected.

The completed section through the rampart showed the ditch and bank with a mixture of clearly heat-affected, reddened stone and unburnt material forming a bank retained by a kerb of unburnt cobbles. The mixed material indicated that construction of the bank took place during a period after the burning and collapse of the primary rampart.

SW section of the trench: post-hole is visible behind the left 1m scale pole; the upper rampart bank is visible to the right with the inner kerb of stones on the left side; facing SW (AOC).

In summary these banks reflect a second phase of re-fortification of the site, which included the formation of the upper rampart and the insertion of a timber palisade ditch. Hazelnut shell from a layer overlying the primary ditch fill was radiocarbon dated to 1036-1192 AD – 11th -12th c. Whilst Birch charcoal from the primary fill of the ditch gave dates of 416-556 AD – 5th-6th c. The dominant wood species was oak and very fragmented pig, goat, sheep bone was also present.

Further evidence for later re-occupation was provided by a relatively clearly defined pit rather close to the surface, with upright angled small packing slabs. It had been constructed through the reddened primary rubble collapse.

Birch charcoal from the lower pit fill was radiocarbon dated to 1018-1155 AD – 11th -12th c. This possible fire-pit identified in the trench section on the inside of the wall had clearly been dug into collapsed stone on the interior of the rampart, post-dating the primary use of it. The content of the two separate fills of charcoal-rich ash and peat-ash are not dissimilar to the description of the 1971 upper occupation layer containing significant quantities of animal bone, ash and peat ash (Small and Cottam 1972).

The upper course of the outer wall face had collapsed out and there was a considerable depth of collapsed, heat-affected stone in the upper layer. The base of the wall was not reached but probably it was 4m tall overall; with a palisade, this would have been significant.

The inner wall face demonstrated similar survival but had a less substantially built face. No evidence of vitrification on either wall face ; and very little in the way of vitrified material on the interior collapse with regards to the exterior. Overall the rampart was 6.5 m wide.

Conclusions As stated Craig Phadrig is classified as an oblong fort similar to E Scotland types such as Finavon, Turin Hill, Dunnideer, Tap o’Noth, Castle Law and Knock Farrell. Many show lron Age and later re-use. They are strongholds and centres of authority, built for reasons we are still understanding, but clearly in places of prominence and strategic locations. Armed with excavation evidence and C14 dates – we now have to start to think about how these sites fit into the changing socio-economic and political picture of the 1st millenium AD.

Excavations are difficult and we still have so much more to learn about these sites and their classification and dating. Unfortunately most of these sites produce few artefacts, so typological dating is difficult and we have to rely on radiocarbon dating. This in itself can be problematic when you have potentially mixed up stratigraphy associated with re-use and destruction.

Further Reading

AOC Data Structure Report 2015.

FSC Archaeological Measured Survey 2014.

FSC Survey and Review 2014.

Headland Archaeology Archaeological Survey of Five Pictish Forts 2011.

With many thanks to Mary Peteranna, presented by James McComas.

I am planning to study the hill fort in Craig phadrig for my dissertation. I would love to be able to get more information on the work you have done there. I would also appreciate it if you could give me a name and email for someone involved with the fort.

LikeLike

Hi Justine. This wasn’t a NOSAS project so I can’t really do better than refer you to the further reading at the bottom of the post which contains several recent reports and surveys, along with contact info. The site is in the care of Forestry Commission Scotland, so that might be the best starting point.

LikeLike