by Fiona Campbell-Howes

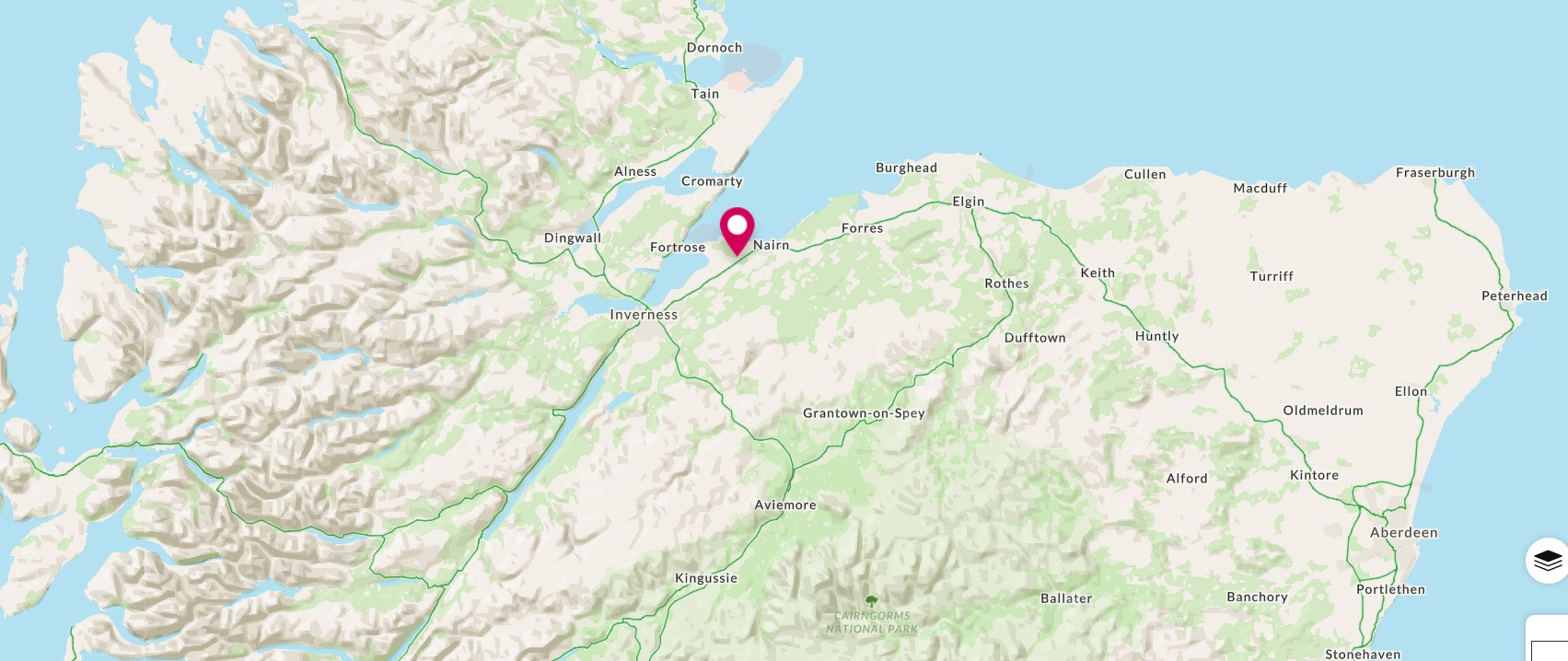

This is the Kebbuck Stone (see Canmore), a relief-carved cross slab dated to the 8th or 9th century, which today sits in the back garden of a cottage near Ardersier.

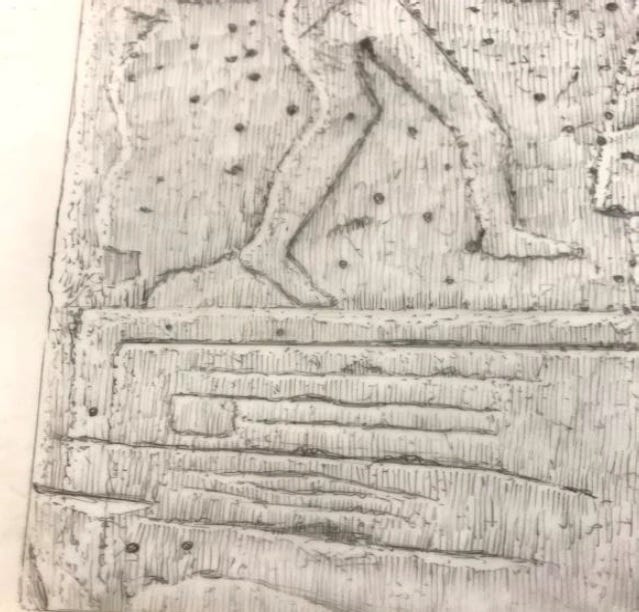

It’s usually overlooked in the corpus of early medieval (“Pictish”) stone sculpture because the carvings have almost completely worn away and the surface of the stone is overgrown with lichen.

It was badly eroded even in 1893, when antiquarian George Bain wrote in his History of Nairnshire:

“The slab is very much wasted from the effects of weathering and ill-usage, but the faint outline of a Celtic cross can still be traced upon one side of it. It is a cross of the earliest form—incised and undecorated—and it would have made a most interesting memorial of early Christian times had it been better preserved.

Bain was right that it would have made an interesting memorial (I think it still does), but he was wrong about the cross being incised and undecorated.

I was only able to make out the top edge of the right-hand arm of it, but there’s a photo on Geograph by Ian R. Maxwell, taken in low evening light, that gives a better idea of what the cross looked like. Ian Maxwell’s photo clearly shows that this was a relief-carved cross, with interlace decoration inside the arms and in the central roundel.

A field report by the Early Medieval Carved Stones Project offers a more accurate description than Bain’s (from Canmore):

“This massive cross-slab must once have looked very impressive, carved in relief on both broad faces, but sadly little can now be made out. The better preserved face shows a large cross with circular armpits, interlace-filled arms and an interlace-filled roundel at the centre of the cross-head. The background to the cross was also filled with ornament, best seen now in the top right-hand area of the stone. The back of the stone is severely defaced.”

I couldn’t make out anything on the back of the stone except for some deep linear grooves, which I’ll come back to later. However, if the Kebbuck Stone was like other relief-carved cross-slabs in the Moray Firth area, it may well originally have had two or more Pictish symbols on its reverse face.

Take the so-called Rodney’s Stone, which was discovered in 1781 in Dyke churchyard, 12 miles east of the Kebbuck Stone. It dates to the same general period, but is very much better preserved:

The stones have a few similarities. They’re roughly the same height (Rodney’s Stone is 1.9m tall; the Kebbuck Stone is 1.7m), both are grey sandstone, and the crosses are of broadly similar style, with square arms, circular armpits and interlace detail.

It’s not hard to imagine that the Kebbuck Stone once looked much like Rodney’s Stone. And, tantalisingly, the reverse face of the latter has a superb set of Pictish symbols carved in high relief: a pair of hippocamps (not usually classed as part of the Pictish symbol canon), a “Pictish beast”, and a double-disc and Z-rod.

I had wondered if 3D scanning technology might be able to detect any trace of original carvings on the reverse face of the Kebbuck Stone. It would be wonderful to find a new Pictish symbol stone hiding in plain sight. Thanks very much to Lorna Morrison of Petty and Ardersier Community Heritage SCIO for letting me know that photogrammetry has been carried out on the Kebbuck Stone by Andy Hickie, revealing faint traces of a cross on the other side. There’s a 3D model on Sketchfab (below) – try the Matcap option for the best view.

Boundary marker or oath-swearing stone?

Two ideas buried in the legends about the stone are probably sound. One is that the stone served as a boundary marker between parishes or landed estates.

Both Bain and the Ordnance Survey Name Book refer to fights between neighbouring lairds, which strongly suggests that the stone was used as a marker to settle land ownership disputes. Over time, this became contorted into a legend of a battle fought over a cheese, or of a resolution celebrated with cheese.

The other, possibly related, is that it was a “covenant stone” – a stone used for the swearing of oaths or witnessing of treaties.

Conor Newman, of the National University of Ireland Galway, has argued very persuasively that cross-slabs in medieval Ireland, Wales and Scotland were used for exactly this purpose. The oath-swearers would signify their assent by drawing their swords across the stone to form a groove.

(He even suggests this may be the origin of the Arthurian sword-in-the-stone legend!)

In a 2009 paper, he writes:

…blade grooves occur with greatest frequency on cross-slabs or cross-inscribed pillar stones, where, as a rule, they are confined to the lower portion of the stone, more often than not close to ground level.

Newman cites a number of stones that seem to have fulfilled this function, noting that they tend to be sacred stones – therefore imbued with a magical power – with connections to important boundaries.

In her (unpublished) 2020 MSc dissertation on Sueno’s Stone, an immense early medieval cross-slab situated about 16 miles east of the Kebbuck Stone, Ruth Loggie makes the connection between Newman’s paper and a series of blade marks found on the lower portion of that stone. Those marks appear in what seems to be a specially-reserved panel, below the cross and a scene interpreted as a royal inauguration.

Is it just a coincidence that the Kebbuck Stone also has multiple linear grooves on its reverse face (below)?

In the stone’s Canmore entry, the Early Medieval Carved Stones Project attributes these deep scores to “misuse, e.g. knife sharpening”. But there are such strong parallels with Conor Newman’s findings that the idea of the Kebbuck Stone being a covenant stone seems (to me, at least) highly plausible.

The site of an early medieval church?

Even if the Kebbuck Stone was a parish boundary marker and/or a covenant stone, these would both probably have been secondary uses; later re-purposings of a convenient landmark.

Its original purpose, like other early medieval cross-slabs, may have been to mark the entrance or boundary to a church enclosure. Any early medieval church building is long gone – although George Bain noted in 1893 that “a heap of stones, probably the ruins of an oratory, lay beside the pillar, but has been removed” – but the cross-bearing stone marking its presence survives.

Possible evidence supporting that theory is that the cottage immediately to the north of the stone sits on a raised mound, quite distinct from the fields and woods surrounding it.

If there was a church here, why was it here, specifically? There are no place-names in the immediate vicinity to give any clues as to what – if any – kind of settlement might have been here in the first millennium AD.

But the nearby village of Ardersier is from the Gaelic “Àird nan Saor”, according to Iain Mac an Tàilleir’s work for the Scottish Parliament, which he translates as “headland of the joiners”.

Is there a clue there? Ardersier sits opposite Fortrose on the other side of the Moray Firth, and would have been a key crossing point from one side of the Firth to the other. And work done by W.J. Watson, and built on by Simon Taylor, is starting to suggest the name Fortrose may be from Pictish foithir-tros, “place of the crossing”.2

The tradition (according to Wikipedia, at least) is that the joiners of Ardersier were working on the great ecclesiastical buildings across the Firth – making them early bridge and tunnel people, commuting across the water to work on the rich monasteries on the opposite shore.

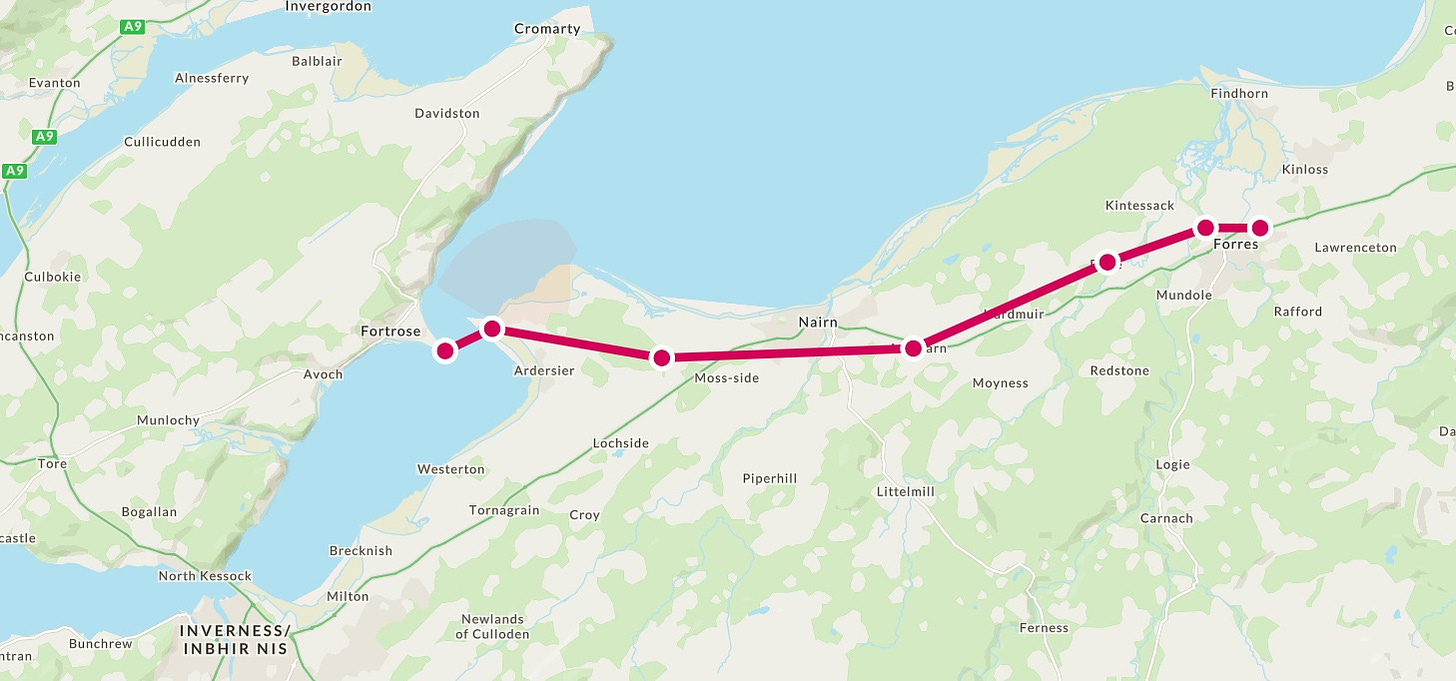

So did the Kebbuck Stone (and its church) sit beside a routeway to Àird nan Saor and the crossing to Fortrose? Perhaps a routeway that led through Moray – passing Sueno’s Stone and Rodney’s Stone en route – and over to the Black Isle?

Of course, I have no way of telling. But I do like the idea of the Kebbuck Stone being an integral part of the early medieval landscape around the Moray Firth, rather than a slightly sad and forgotten sandstone slab sitting in someone’s back garden.

And if this blog helps to reinstate it in that landscape, that would make me very happy.

- The above article is reproduced in edited form from the blog Becoming an Early Medievalist, with kind permission of the author. The original blog post can be viewed here, which contains more information on legends connected with the stone.

Very interesting read !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi

Thanks for forwarding this.

I wrote to Fiona to mention Andy Hickies 3D pictures I need to get them on to the HER its on the to do list (still) after the ARCH Kirkhill course is finished.

Our stone might be a bit rubbish now, but its exciting to think it could be in its original location something to look at for the future pilgrimage routes, etc along the firth. It is on a mound, on an old route with a well nearby (as always), and has a (defensible) steeply dropping bank behind it where the woods are now. The description in Allen & Anderson is that it has been shamefully abused https://archive.org/details/earlychristianmo03alle/page/n149/mode/2up

Another reason to find Cawdors old estate maps or any Diocese of Ross maps that might exist…

Cheers

Lorna

Sent from Mail for Windows

LikeLike

i am a retired police officer and amateur writer and when I began looking at Pictish Standing Stones about a month ago, I had a notion that some could act like ‘road signs’, showing a route way, and that route I felt in terms of northern Pictland could be Aberdeen to Rosemarkie, Fortrose, then north to Cromarty/Portmahomack? One monastery to another? I had been looking for a stone to be a part of that around Nairn………..this might be the one??

LikeLike