by Roland Spencer-Jones (NOSAS)

In 1756 a young man had been sent by his employers to Coigach, a rough, remote area on the west coast of Scotland, just north of Ullapool. He wrote to those employers on 21st July:

The estate of Coigach is a very large country, and the subject difficult and tedious to measure, being little else but high mountains with scattered woods, steep rocky places, and a number of lochs in the valleys, which with the great distance there is between houses makes me obliged to sleep in the open fields for several nights together, which is dangerous in a climate where so much rain falls. I wish (you) would condescend to allow me a tent or otherwise I’ll have great difficulty to go through. There is no such thing as sleeping in their houses in the summer time, they are so full of vermin[1].

The man was Peter May, an Aberdeenshire land surveyor, and his employers were the Commissioners for the Forfeited Estates. After Culloden the British (London!) government forfeited, and therefore took possession of, the estates that had “come out” in the 1745 rebellion. Six years later an annexing Act was passed, in 1752, and three years later the Commissioners for the Forfeited Estates finally met. They wanted to know what lands they now administered, and also wanted to improve the economic performance of those lands. They therefore appointed land surveyors for the main 13 estates that were their responsibility, including the estates of Cromartie (the Mackenzie Estate, and hence Coigach) and Lovat. Peter May was appointed to these two estates, and produced a series of maps, surveying the entirety of the estate ground.

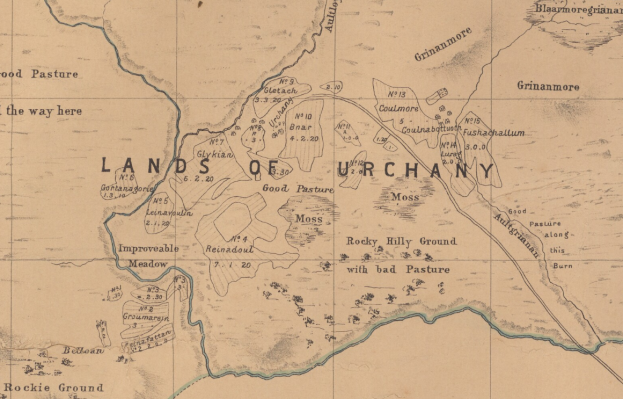

I had seen a hand-drawn copy of one of these Peter May maps, pertaining to the Barony of Kilmorack, when NOSAS had undertaken a survey of the lands of Urchany, a multi-period deserted settlement west of Beauly. I was keen to see and study the original, which was said to be in the Lovat Estate offices in Beauly. After a little persistence, I was allowed to look at the map, which was a valuable experience. I then realised that the office contained many more maps that could also be relevant to the survey. Not all of the maps were known, even to the estate manager. I asked him if I could catalogue and therefore research the whole map archive. He said yes!So, throughout 2017 I embarked on a full cataloguing of the maps, completed by autumn that year. The end result was a detailed list of over 400 maps, and a book of 64 maps (1798-1800) by George Brown. Some of these maps were well known to the estate, some hadn’t been looked at for decades. The list included 5 precious maps by Peter May, out of the eight he was known to have made up for the Lovat Estate. The majority of the maps were made in the 19th century. They varied in size, condition, detail and relevance. Some had been used in dispositions.

There had always been an aspiration to digitise the maps, and then upload them to the website of the National Library of Scotland (NLS), similar to the Dumfries Archival Map Project (DAMP) However, this suddenly became a possibility in early 2018 as the estate considered moving its office. The maps were taking up space and could alternatively be deposited in the Highland Archive. However, a digital copy of the maps on the office computers would mean they could still be easily consulted, even if the originals were in Inverness, 13 miles away.

So, a decision was made to hire an A0 flat-bed Versascan scanner from GenusIT in Warwickshire and to scan the entire map archive. The labour to do this would be provided by NOSAS members. During a very focussed and energetic week in April 2018 all the maps were processed in what can only be called a production line. A small team of people worked hard to process each map – locate it, unroll it, dust and clean it, check it against the list, pass it to the scanning team who laid it on the flat-bed, while the scanner operator controlled the scanning process on a computer. The resultant huge TIFF files were then stored and backed up at the end of each day.

At the end of the week, we had scanned over 400 maps plus the 136 pages in the George Brown book, plus 17 maps from other estates. This generated >200GB of data, including 900 TIFF images, many of which individually exceeded 500MB each. 57 maps were too large to be scanned in one go, even on the 0.8m x 1.2m flat-bed surface. They were scanned in parts. One huge map required seven scans. The images were then processed (including rotating, cropping, and a JPEG copy made). The NLS then received the maps, stitched together those that were in separate scanned images, and are progressively uploading them to their website.

Eventually, there should be over 360 maps on the NLS website.

This includes a collection of 17 maps from six other local estates. The project would not have happened without the support and encouragement of :

- The Lovat Estate, in particular the estate manager, Iain Shepherd, and Simon Fraser 16th Lord Lovat.

- Archie McConnell, of the Dumfries Archival Mapping Project. They had trod this road before.

- Chris Fleet and his colleagues at the National Library of Scotland.

- The Trustees of NOSAS who immediately recognised the importance and value of the endeavour.

- Finally, that small band of NOSAS scanners who dedicated their week to an almost industrial process.

What’s the value of these online maps?

- They provide snapshots of historical time. Most of the maps are dated, so comparing parts of the estate over time allows change to be observed.

- The maps are works of art. The penmanship and calligraphic skills reflect the skills of the surveyors and cartographers. These maps were made with ink and quill, with no margin for mistakes.

- They provide a sequencing of cartographic convention, eg in the depiction of houses.

- They provide historical evidence as a basis for future archaeological survey and discovery.

[1] Papers on Peter May, Land Surveyor 1749-1793, edited by Iain Adams, Scottish History Society 1979.

Pingback: Lovat Highland Estates mapping (1750s–1960s) – Heritage Hunter

I am interested in purchasing a digital copy of the Lovat estate maps relating to the period 1752-774 when the estate was forfeited. I catalogued the extensive Forfeited Estates Papers for the national archive and know that when the estate was returned to the Lovat heir in 1774 a large number of maps were gifted to him from the FEP. I would be delighted to hear from you and have the opportuniity to see Peter May again!

LikeLike